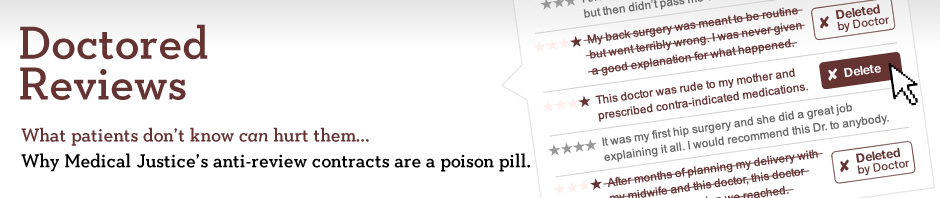

Anti-Review Contracts Might Appear to Solve One Type of Legal Problem for You, but They May Be Creating Other Legal and Ethical Risks

Anti-review contracts are risky choices legally and ethically. By using one, you may be exposing yourself to unnecessary and undesirable legal and ethical challenges.

The Legal Problems

Anti-review contracts that categorically ban patient reviews are legally dubious. New York v. Network Associates, 758 N.Y.S.2d 466 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2003), involved an enforcement action by the New York Attorney General’s office, where the court held that a contract prohibiting consumer reviews violated consumer protection laws. Although the Medical Justice contract has not been the subject of a similar enforcement action (at least, not yet), doctors who use the Medical Justice contract to suppress patients’ reviews may fare no better than Network Associates did. Therefore, simply by including a patient review ban in the contract, doctors run the risk of violating consumer protection laws and exposing themselves to an enforcement action by state and federal consumer protection agencies.

In addition, using the contract could lead to problems with the Office of Civil Rights in the Department of Health and Human Services, which enforces HIPAA. The OCR has already stopped one doctor from requiring that patients sign an anti-review provision in exchange for maintaining patient privacy. Continuing to use these provisions could lead to more enforcement in the future.

Bringing an actual lawsuit against a patient for breaching the anti-review ban doesn’t seem like a good choice either. In addition to the inherent risks of suing your customers, such lawsuits might be considered “SLAPPs” (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation). A number of states have anti-SLAPP laws that, among other remedies, require the plaintiff to pay the defendant’s attorneys fees. In other words, by bringing a lawsuit over the anti-review ban, the doctor may end up writing a check to the patient and her attorney.

Using a version of the anti-review contract that doesn’t ban reviews but takes a prospective copyright assignment of patients’ reviews tries to sidestep these concerns, but it creates other problems. We expect courts will frown on these copyright assignments, both on policy grounds (because, after all, they are designed to squelch negative consumer reviews) and procedural grounds (because they are a completely unexpected provision buried in a large stack of papers presented to new patients at a time when many of them are emotionally or physically vulnerable). If the ownership assignment fails, then actually using the contract as designed—to send a copyright takedown notice over a patient review—could lead to liability under 17 U.S.C. §512(f), which exposes senders of bogus copyright complaints to money damages in a lawsuit. For an example of a successful 512(f) lawsuit, see this case.

Even if the assignment works, you can’t send a copyright takedown notice unless you are sure the author is a patient who signed the contract. This may be tough to verify if the review is posted by an anonymous or pseudonymous author. In those cases, sending a copyright takedown notice could expose you to 512(f) liability if you claim a copyright in a review but didn’t actually get the copyright assigned to you.

In fact, Medical Justice appears to encourage doctors to use anti-review contracts in a manner that almost certainly violates 17 U.S.C. §512(f). In this interview, Medical Justice CEO Dr. Jeffrey Segal suggests the contracts help remove fictitious posts by competitors and ex-spouses who might be pretending to be patients. However, neither of these reviewers would have signed the doctors’ contracts containing the copyright assignment, and thus the doctors cannot claim to own copyrights by those reviewers. Without any claim to owning the copyright, doctors would be exposed to a 512(f) claim for sending takedown notices in the circumstances that Dr. Segal is advocating.

Even if you only send copyright takedown notices in response to reviews by actual patients who signed the copyright assignment, then you may be committing a privacy violation by identifying the reviewer as one of your patients to the takedown notice recipient. Therefore, taking advantage of the central benefit of the anti-review contract—the ability to send copyright takedown notices—could create significant legal exposure to you. You can avoid risking that legal exposure by avoiding the use of these contracts.

The Ethical Problems

These contracts also raise ethical concerns, including:

Putting your financial interests ahead of your patients’ interests: The AMA Code of Ethics calls on doctors to put their patients’ interests before their own financial interest. (See AMA Ethics Opinion 8.03). Anti-review contracts potentially violate this tenet. First, by forcing patients to sign anti-review contracts, doctors are valuing their reputations—and the associated financial benefits—above other considerations, including the effect on patients. Indeed, Medical Justice’s contract typically notes that “Physician has invested significant financial and marketing resources in developing the practice,” making it clear that the contract is seeking to protect the doctor’s financial interests. Second, a doctor’s “privacy” promise to forego marketing opportunities implies that those marketing opportunities aren’t in patients’ best interests. If not, then foregoing them is the ethical choice, whether the patient consents or not.

Breaching patient confidentiality: Identifying the names of your patients to enforce medical gag orders can potentially violate AMA Ethics Opinion 10.01(4).

[Note: we initially posted this page in 2011. A few months later, Medical Justice “retired” its form. In 2016, Congress enacted the Consumer Review Fairness Act banning anti-review contracts.]